This article is not directly KDE-related, so you might want to skip it. But if you’re interested in a cool project simplifying the way software is distributed on Linux, read on! ![]()

At time, if you develop a new application “Foo”, you as an upstream developer let other experienced people distribute your application in Linux-Distribution X through a package. Packaging an application is not as easy as some people think, a package of high quality requires some work. And the package wants to be maintained. The upstream -> downstream way we have at time works very nice, although there are some problems:

- It takes time for downstream people (packagers) to package a new bugfix release / a new major upstream release

- If a distribution is frozen (=stable), new upstream major releases aren’t sent to the archives anymore, so users will use an outdated version of an application

- Some stuff is just not packaged, think of proprietary software as an example. But also free software needs someone to step in an package the stuff.

- There are thousands of Linux-distributions. An application needs to be packaged for every single distribution (in the worst case)

To make new software available for users of stable distributions and to offer a possibility for everyone to package stuff, Ubuntu invented [Update] The OpenSUSE Build Service offers a similar, but cross-distro alternative and has been published earlier than Ubuntu’s PPAs. [/Update] the so-called PPAs.

PPAs have great advantages:

- You can install PPAs easily

- You always get fresh updates using the generic Update-Manager

- It is nicely integrated with other parts of the system

People who know me might now want to skip the next section – I am a very well-known critic of PPAs ![]() Despite all the great advantages, PPAs also have their issues:

Despite all the great advantages, PPAs also have their issues:

- Security: If a package contains malware, it will have root-access to your full system. You’re practically giving someone else root-access to your system by installing a PPA.

- Quality: Packaging is not only taking the upstream tarball and putting it into a DEB package. There are a lot of quality standards to comply with, if you want a high-quality package. The quality guidelines are defined to keep the Distribution working & stable. Some people might not know how to create a sane package and there is a serious risk to damage the system sooner or later with a “bad” package.

- Upgrades: If you install new versions of a package, old packages provided by your distributor get replaced. And even if you only add new packages, you might break your distribution’s upgrade-path, so an upgrade to a newer distribution-release might fail. (nobody tests with every PPA installed)

- Ubuntu-Centric: PPAs are Ubuntu-only. There’s no Fedora support and no Debian support too. A cross-distro solution would be better.

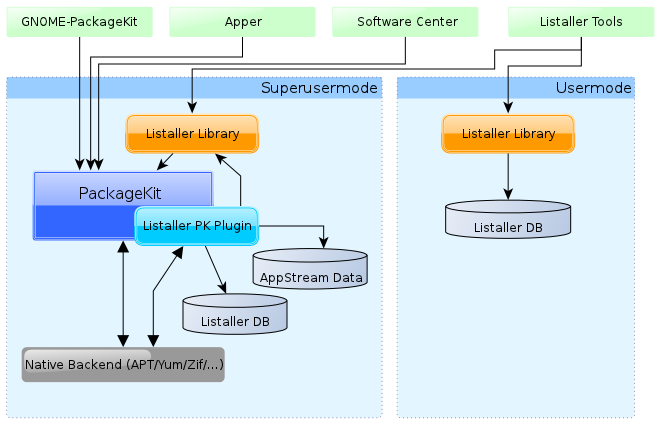

Because of these issues, I started Listaller, a new approach of a cross-distro software installer. Listaller is based on two great projects: PackageKit and AppStream. The development started years ago, but all old code has been thrown away with the availability of a stable PackageKit and the AppStream project, which covers some Listaller’s former project goals and will reach them in a much better and more generic way than Listaller could’ve done. Listaller is now rewritten in the Vala programming language.

The project was started to offer upstreams the ability to provide cross-distro packages of their applications. This means Listaller was designed to install applications and not libraries or system-components. So, Listaller was not designed to replace package formats like RPM or DEB or to replace package managers like APT/Yum/Zypper/etc. It’s main goal is to extend these systems to offer cross-distro application installations.

The “package”-format of Listaller is a tarball with the extension “.ipk” (Installation-Package) containing a GPG-signature, a XZ-compressed archive with XML control data and a (also compressed) archive with the payload data. This is very similar to the structure of a Debian archive.

Because Listaller works as a PackageKit plugin, all tools using PackageKit will magically get support for Listaller too. So you can remove Listaller-installed software through Apper on KDE and with GNOME-PackageKit on GNOME. Users won’t notice the difference. Same also applies to updates: Users will only see one updater application. This will avoid having many different UIs which do all the same.

How are dependencies handled? By default, Listaller always tries to use native distribution packages as dependency providers. (It searches them through PackageKit) If this does not work, it can make use of ZeroInstall feeds too. (this feature is under construction at time) Listaller distinguishes between applications, dependencies or resources and frameworks. Applications are packaged in an IPK package, while dependencies are fetched from somewhere else and can be used by many applications. Frameworks are something like D-Bus, PolicyKit, PackageKit, Nepomuk or Akonadi, which relies on being integrated with the system. Listaller will never try to install a framework. Frameworks always have to be provided by the distributor. (This has security reasons too, also Listaller just can’t do this cause of it’s design.)

And what about relocatable applications? Well, that’s a big issue. Binaries on Linux usually have paths to their data hardcoded, so they will always search in e.g. “$prefix/share/foo”. But Listaller puts applications and their data into /opt by default, so binaries need to find data independent where they are. To achieve this, we have code called “BinReloc”. Listaller inherited this from the Autopackage project, which has been merged into Listaller some time ago. BinReloc allows software developers to create relocatable applications by integrating it into their applications. For some people this is not necessary anymore: Qt4 already provides some nice methods to create relocatable apps.

To make installed apps find their libraries, every Listaller application is executed using a tool called “runapp”. This tool will set the LD_LIBRARY_PATH variable and run the applications. So you can easily use Listaller-installed tools in scripts. This also avoids collisions with applications in /usr/bin.

Is it secure? Yes, Listaller is secure. Every package should be signed, if it is not, the installer will reject it by default. (Unless you change the settings ![]() ) Updating software is easily possible, and Listaller applications will never conflict with native distribution applications, so upgrading a distro is safe. Also, the “runapp” tool is able to execute every newly installed application in a sandbox first, so you can test the application. IPK packages don’t have much possibilities to damage the system, because they don’t contain custom scripts. So, yes, Listaller is secure. Only the user could do the wrong thing

) Updating software is easily possible, and Listaller applications will never conflict with native distribution applications, so upgrading a distro is safe. Also, the “runapp” tool is able to execute every newly installed application in a sandbox first, so you can test the application. IPK packages don’t have much possibilities to damage the system, because they don’t contain custom scripts. So, yes, Listaller is secure. Only the user could do the wrong thing ![]()

Okay, this was a quick, but still far too long information about what keeps me busy. ![]() Listaller has very few developers and to be honest, there was a time where I thought this project would fail. But now I’m sure that working on it is a good activity

Listaller has very few developers and to be honest, there was a time where I thought this project would fail. But now I’m sure that working on it is a good activity ![]() At time, there are only GNOME-frontends available for Listaller. This is because the Qt bindings aren’t updated and because of me, who is eager to try Smoke-GObject on this project

At time, there are only GNOME-frontends available for Listaller. This is because the Qt bindings aren’t updated and because of me, who is eager to try Smoke-GObject on this project ![]()

So, thanks for reading! And I promise, the next post will be more KDE-centric again ![]()